Jules Verne, Vingt Mille Lieues sous les mers, Paris, J. Hetzel, 1871, p. 392.

Maïté Seimetz shapes encounters that are felt as much as they are seen.

At first glance, the objects she designs look as if they were once alive. Each joint, claw, and limb is articulated precisely to fulfill a function–hold in place a piece of glass, frame a reflective surface or encase a lightbulb. Upon closer examination, its texture suggests there is something more behind its appearance. Lacquer executed with meticulous craftsmanship renders its bodily parts and concentric layers of fibrous material reveal its digital provenance. When handled, their shape, texture, and weight speak back—manifesting a kind of presence that feels both intimate and otherworldly. Her work introduces a sense of magic and enchantment into objects we would usually consider purely functional. These are not just tools or furnishings, but presences that seem to carry moods, intentions, or quiet narratives. She crafts the way these objects look as much as the sensorial experience that surrounds them. In doing so, she challenges the boundary between the designed and the dreamt, suggesting that even the most practical object can hold mystery.

I first came into contact with Maïté’s work at an event in London curated by Gubns, a platform dedicated to showcasing objects by architect-makers operating outside of traditional practice. Her objects stood out immediately—not despite their digital origins, but because of the care and precision they embodied, qualities that many of the hand-wrought pieces around them only seemed to perform. I took a selfie on one of her mirrors hanging from the ceiling. I remember how that reflective surface concealed in its over-sized, over-articulated frame resembled a portal to another dimension.

Over a remote lunchtime conversation, Maïté and I spoke about the soul of functional objects, forms that feel alive, and craft not as nostalgia, but as discipline—one that, even when shaped by technology, must resist becoming mere style.

Interview by Asiel Nuñez | Edition by Juan Cantú and Candela de Bortoli | Photography by Classics Of The Future, unless otherwise specified. | Video by Tomas Orrego

MARC FORNES IN HIS STUDIO, AMONG PROTOTYPES OF HIS WORK.

THEVERYMANY STUDIO ENTRANCE

MARC FORNE’S JACKET AT THE STUDIO

Asiel Nuñez: You like to refer to your work as “engineering wonder”. Can you explain what this term means to you?

Marc Fornes: I think the phrase engineering wonder carries multiple layers. It speaks to the tension—and the balance—between technical precision and emotional experience. On the one hand, it's about the art of engineering, such as designing a bridge—a discipline grounded in performance, structure, and rigour. But on the other hand, it's also about fantasy—about creating spaces that transport you, that momentarily lift you out of reality. While our research is deeply serious, the outcome is meant to make you forget all that engineering and simply feel. It's about the moment you lose yourself, first in the environment, then in your own thoughts. So, for us, engineering wonder isn’t just a phrase; it’s a practice of crafting that sense of awe with intention and specificity.

Where does your fascination with the duality between engineering and wonder, or experience, come from?

I think it started with where I grew up, right on the border between France and Germany. I’m French, I carry a French passport, but culturally, so much around me was German—the food, the traditions, the mentality. Just across the border was the Autobahn, that stretch of highway with no speed limit. And I’ve always been fascinated by it. Because you don’t just drive on the Autobahn with any car. You need something engineered for it—something that can go fast, brake fast, respond instantly to the tiniest shift in conditions. That’s precision. That’s control.

But once you’re driving, you don’t want to think about all that. You want to just enjoy the ride. You want to lose yourself in the motion, the momentum, the thrill. And to me, that’s exactly what our work is about. In the studio, everything is about detail—the technical logic, the making, the constraints. But the end result? That should feel effortless. You shouldn't have to think about how it was made. You should just feel something.

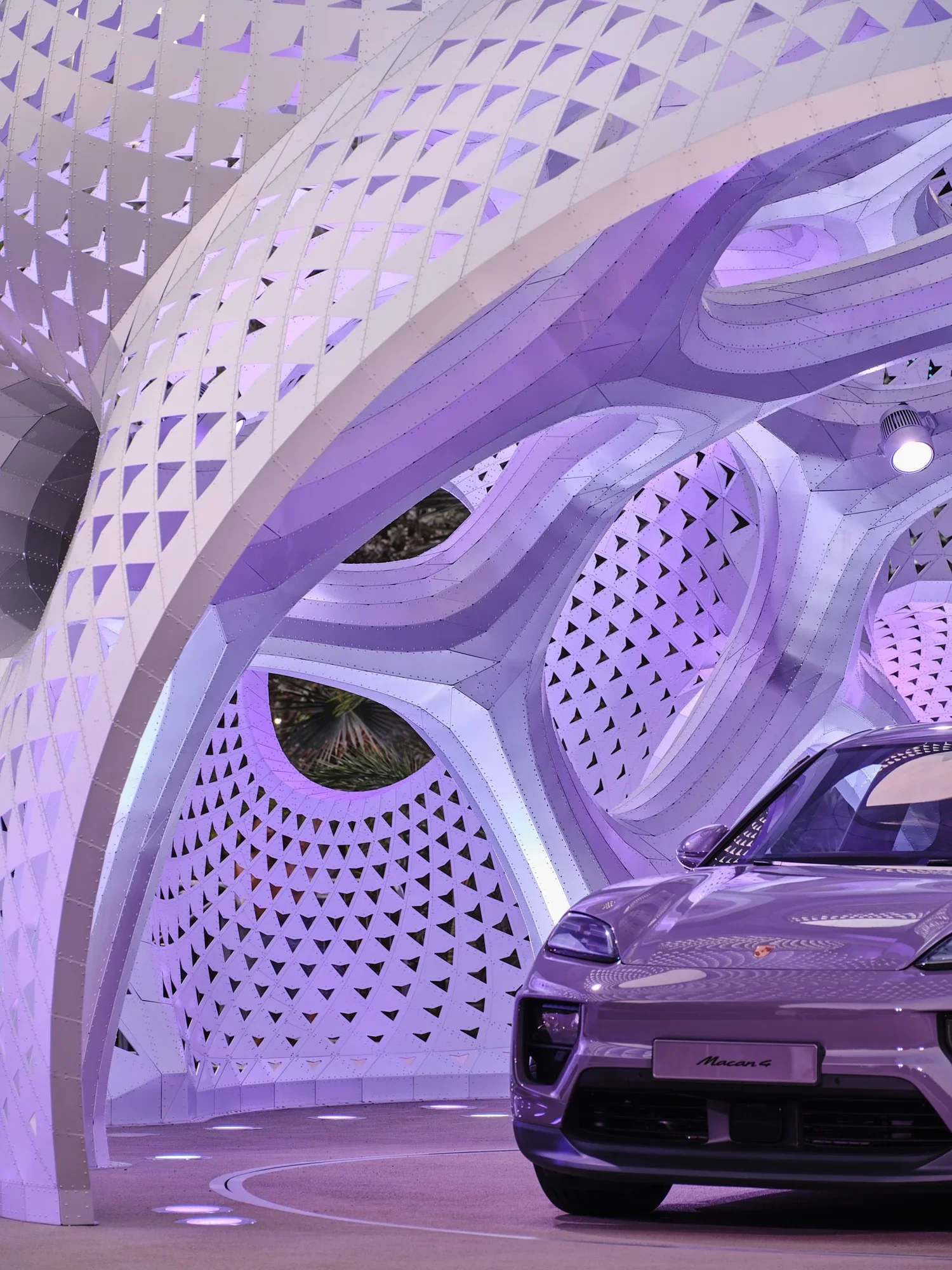

So, in a way, our projects are like those high-performance machines—deeply engineered, but built to deliver an experience that feels fluid, emotional, even dreamy. That’s why I often mention Porsche, for example. German engineering is a great parallel to what we do: it’s extremely precise, but it exists to support a kind of escape.

You recently designed a two-car garage for Porsche, and you own a Porsche yourself! Would you say you are a Porsche fan?

Yes, I am! With Porsche, especially for those who really know the brand, it’s about what’s inside. I’m particularly fascinated by the air-cooled models—a very specific era that represents a kind of purity, German engineering at its finest. These are cars designed to be driven, and driven fast.

I once spoke with Michael Mauer [the current Chief Designer at Porsche and responsible for the 911 models], and he told me something that really stuck. At Porsche, they’re intentionally keeping as few digital controls as possible. Because when you’re driving over 200 kilometres per hour on the Autobahn, you can’t afford to scroll through menus. You need to be able to let go and grab back instantly. So, they keep physical buttons on the steering wheel—it’s about tactile control, about immediacy. You don’t want something square or stylised—you want performance you don’t have to think about. He even joked that Porsche might be the last brand to keep a round steering wheel. And that actually makes a lot of sense.

That fascinates me, because it’s the same in our practice. At THEVERYMANY, we’re detail-oriented and equally obsessed with precision. We’ll spend hours debating which type of rivet to use, even if they all have the same structural capacity. For most architects, that’s a decision the structural engineer makes. But for us, that’s just the starting point. We don’t stop at construction documentation. We go all the way to what we call fabrication files, essentially the shop drawings for the entire project. There’s a shared commitment to control, to refinement—not for its own sake, but in service of something that ultimately feels effortless.

I’ve noticed a lot of toy cars around the office.

Yes! I’ve always been fascinated by vintage toy cars, especially one specific brand called Joustra, short for Jouets de Strasbourg [Toys of Strasbourg]. I’m actually from Strasbourg in France, and many of those models from the '70s and '80s were Porsches, which I loved for two reasons. First, there’s the sense of pursuit, almost like developing a project. It’s about the search: finding the right people, the right design, the right fit. Then there’s that second phase—once the car is made and it’s out in the world. Just like a finished project, it’s no longer in your hands. It takes on a life of its own.

And I love the fact that none of the toys that I collect are pristine. They will have a broken windshield and some patina behind the wheels, just as a car would age to some extent.

And for me, there's nothing worse than actually discovering one of those still in its original box. It means it has never been played with, which is the worst nightmare and failure of the toy designer.

MARC FORNES X PORSCHE MY TWO CARS GARAGE’ Photo © DOUBLESPACE

THEVERYMANY STUDIO ENTRANCE

ONE OF MARC FORNES’S JOUSTRA TOY CARS

‘MY TWO-CAR GARAGE’ PROJECT MODEL

ARTIST DANIEL ARSHAM’S PORSCHE DESIGN AT TVM STUDIO

‘THIS IS MY DAUGHTER’S FIRST CAR, WHICH I’M VERY PASSIONATE ABOUT. WE HAD TO BRING IT FROM EUROPE, BECAUSE IT WAS A PRESENT FROM HER GRANDPARENTS, SO IT HAD TO BE PACKED AS SMALL AS POSSIBLE INTO THE AIRPLANE.’

That is interesting! Your work being rooted in controlled engineering and precise craftsmanship, how do you approach failure?

For a long time, I gave a lecture series focused entirely on our failures. But failure, in this context, wasn’t always dramatic, though that did happen from time to time. We had some early projects actually collapse inside a gallery! More often, though, it was about recognising the small, embedded failures in every project. You start to see that something doesn’t need to be a complete disaster to be considered a failure. Sometimes it just means things could have been done faster or more efficiently. Or maybe it works, but it’s not scalable.

For instance, I’ve hit the upper limits of what’s possible with certain material systems. That, too, is a kind of failure. It pushes you to step back and ask: how do I scale this up? Does that mean fewer parts? Bigger parts? Thicker material? And how will those changes ripple through the entire design approach?

We’ve learned a huge amount through these kinds of setbacks. With aluminium, for example, we could probably write a PhD on what we now know about painting and protecting it. But again, I really want to stress that failure doesn’t have to mean catastrophe. It can just mean that next time, you realise the paint finish looks great, but it takes too long to apply. Or it’s too expensive. Or it looks great, but touch-ups are a nightmare. Or maybe the touch-ups work well, but the finish doesn’t hold up as well as the previous one. Those are all small failures, but they’re invaluable lessons.

You seem to work a lot with aluminium.

Over time, we’ve primarily used aluminium—particularly very thin sheets—for several reasons.

First, aluminium doesn’t rust, so it holds up exceptionally well over time. You’re never at risk of losing the structure due to corrosion. Second, it’s incredibly lightweight. As you can probably tell from our prototypes, one of the core principles in the studio is that every piece, every element of the 3D puzzle, should be able to be carried by hand. We never want to rely on cranes or heavy-lifting equipment during the installation process. Aluminium also makes assembly easier. It’s soft enough to bend to a specific radius and curves without creasing or marking, which gives us a lot of flexibility in form.

That said, aluminium isn’t the only material we use. In our early projects, we experimented with all sorts of ultra-thin materials. [Points to a model in the studio] that one, for example, is made from extremely thin veneer.

We’ve also explored composites. In fact, we created one of the first carbon fibre shells ever used in architecture. But when you're doing public work and presenting your materials to a committee, aluminium tends to be much easier to defend and less intimidating than composites, which can still feel experimental to some.